Originally published on March 17, 2019

///

American country music artist Jason Aldean sings in “Fly over States” about two men flying first class from New York to Los Angeles and wondering who would want to live in the sparsely populated Midwestern region below them, “[j]ust a bunch of square cornfields and wheat farms, “Man it all looks the same. […] Who’d want to live down there in the middle of nowhere.” Aldean has an answer: “Feel that freedom on your face, breathe in all that open space.”

There are good reasons to live in less populated areas, and many of us who work in large cities at times romanticize about a simpler life with less traffic. But a simpler life with less traffic also often comes with fewer employment opportunities, especially in the more highly-paid technology sector, which has led many to leave rural areas in search of good and high-paying jobs.

Representative Ro Khanna, a Democratic member of the House of Representatives from California’s 17th District, which includes Silicon Valley, wants to solve the problem of the lack of high quality jobs in rural areas. His solution is to have the federal government fund the development of a tech proficient workforce in rural America by making available about $50-100 million dollars to each of fifty colleges and universities in areas designated as “opportunity zones.” Opportunity zones are economically-distressed communities, as defined by the U.S. Treasury Department. Almost half of the counties in the U.S. have opportunity zones.

Khanna’s bill will fund colleges to educate students in technology fields where companies, like the ones in Silicon Valley, have a need. These companies currently outsource over 211,000 jobs to countries like Malaysia and Brazil, according to Mr. Khanna in a recent editorial in the New York Times.[1] He proposes that Americans in rural areas could do these jobs without the need to leave their hometowns.

No doubt, bringing high-tech jobs that are currently being outsourced back to the U.S. can provide opportunities to those who want or need jobs that allow them to work from home. However, Khanna’s proposal also has the risk of actually further increasing the rural-urban gap.

First, more than 80% of Americans no longer live and work in rural areas[2], and telecommuting jobs are not just found in rural areas. According to the 2017 American Community Survey[3], about 5% of the 148 million workers age 16 and above telecommute full time. Only about 11% of those who telecommute full-time live in rural or mostly rural counties, whereas over 70% of those who telecommute full-time live in counties with a workforce of at least 100,000. As things exist today, most of the additional high-tech jobs will therefore likely go to counties that are neither small nor rural.

Second, full-time telecommuting rarely comes with professional advancement opportunities that are open to those who work (mostly) on site. This lack of opportunity for advancement is particularly detrimental in the first decade of employment when earnings increase most rapidly.

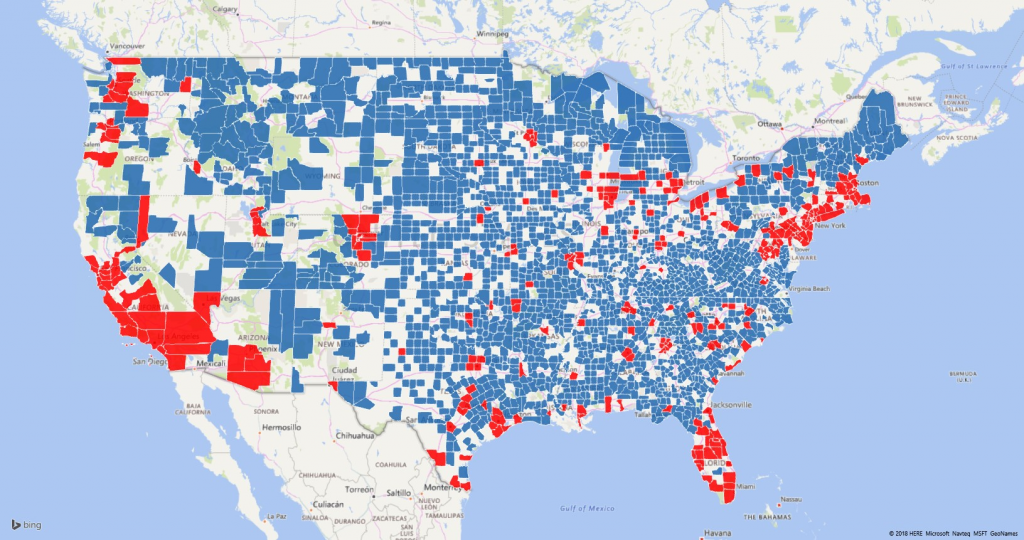

Third, most of the U.S. is sparsely populated (Figure 1). The fifty colleges who would receive funding in Khanna’s bill would therefore likely be unable to reach many students unless the programs are delivered online. Mr. Khanna’s proposal might also fall far short to meet the demand if he continues to target colleges in opportunity zones like the West Virginia University Institute of Technology, which he portrays in the NYT editorial as “a model [that equips] students with practical degrees or credentials that lead to jobs.”

Figure 1: Rural and mostly rural counties (blue) and counties with at least 100,000 workers of age 16 and above (red).[4]

The size of West Virginia University Institute of Technology with about 1,600 students, including about 150 students enrolled in online programs, pales in comparison to the many large universities that now offer online programs including 400 free online Ivy League university courses.[5] Some of these, like Western Governors University or Southern New Hampshire University list online student enrollment of over 110,000 and over 90,000 students, respectively, on their websites.[6] Western Governors University is located in Salt Lake City, Utah; Southern New Hampshire University is in Manchester, New Hampshire. Neither one is located in an opportunity zone. Universities in the U.S. could easily absorb the additional number of students in their online programs to fill over the next several years the more than 211,000 jobs that are currently outsourced offshore. This additional source of students may be particularly welcome in the face of largely stagnating and eventual decreasing numbers of high school graduates over the next 10-15 years.[7] The money might be better spent on scholarships for students in rural areas than on colleges to develop or expand programs.

To take advantage of online programs or telecommuting, broadband internet access is needed. The U.S. still lacks universal broadband access, in particular in rural areas. Khanna is well aware of this and mentioned in his editorial the January 2017 White Paper on Improving the Nation’s Digital Infrastructure from the Federal Communications Commission[8], which estimated that about $80 billion would be needed to increase high-speed internet coverage in the U.S. from the 86% in 2016 to 100%. The White Paper recognizes that “broadband is a foundation for economic activity across many sectors.” Investments in broadband would go a long way and likely spur economic development in underserved areas. But even universal broadband access does not solve the issues we raised about 100% telecommuting.

We need to find ways to connect rural communities better to urban areas with better economic opportunities. Population centers in the past often developed along transportation lines—railroads at first, then highways. To expand the feasibility of commuting from less populated areas to thriving economic regions, high-speed transportation is needed. In our large congested metropolitan areas, commuting for an hour is not unusual. The fastest high-speed trains reach speeds of over 250 mph, which makes distances of 200 miles come within a reasonable commuting distance, even considering that it takes time to get from home to the nearest station and then from the destination station to the workplace. Technology can further assist to make the train ride a productive part of the workday. High-speed trains could connect economic hubs and open partial telecommuting to people along the tracks who could stay in rural areas but still be part of the digital future without feeling that they simply took the place of workers in Malaysia and Brazil once outsourcing will have lost its economic advantage.

[1] Khanna, Ro. Spread the Digital Wealth. The New York Times. December, 30, 2018. (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/30/opinion/tech-rural-america.html; accessed on December 31, 2018)

[2] The Census Bureau defines rural and mostly rural counties as having less than 50% of the population of the county being represented by the urban population.

[3] https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_16_5YR_S0801&prodType=table (accessed on January 2, 2019)

[4] Data Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: Sex of Workers by Means of Transportation (https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk; accessed on December 31, 2018) was used to identify the counties with at least 100,000 workers of age 16 and above. The 2010 Census Urban Lists Records files were used to identify the rural and mostly rural counties (https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/reference/ua/PctUrbanRural_County.xls; accessed on January 6, 2019).

[5] 400 free Ivy League university courses you can take online. Dhah, Dhawal. Quartz. January 4, 2019. (https://qz.com/1514408/400-free-ivy-league-university-courses-you-can-take-online-in-2019/amp/?hss_channel=tw-13558642; accessed on January 8, 2019)

[6] WGU (https://www.wgu.edu/about/students-graduates.html; accessed on January 6, 2019); SNHU (https://www.snhu.edu/about-us; accessed on January 6, 2019)

[7] Knocking at the College Door. Projections of High School Graduates through 2032. WICHE. (https://knocking.wiche.edu/; accessed on January 5, 2019)

[8] Improving the Nation’s Digital Infrastructure. White Paper. 2017. Federal Communication Commission. (https://www.fcc.gov/document/improving-nations-digital-infrastructure; accessed on January 4, 2019)